Sakasa Kebari

The Sakasa Kebari, or reverse hackle fly is probably the iconic "tenkara fly." At least in the US. (I have since learned that in Japan more tenkara fly patterns are tied in the "Futsu" style, in which the hackle stands straight out from the hook shank, and looks for all the world like a slightly sparse dry fly without a tail, or in the "Jun" style, in which the hackle slants back towards the hook bend, as in most Western wet flies.) Dr. Ishigaki's fly is a variant of the Sakasa style, using rooster hackle rather than the more traditional hen pheasant soft hackle feather. I generally tie the sakasa kebari with partridge. Partridge feathers wrap well, they're the right size, and on one skin you get both brown and grey feathers. On a hen pheasant skin, most of the feathers will be too large.

I am struck by the similarity of the Japanese sakasa kebari and the Italian pesca a mosca Valsesiana flies. Both have reverse hackles, and both flies are "worked" or "manipulated" when they are fished. The reverse soft hackle pulses as the Japanese use their "invitation" technique and as the Italians "dibble the top dropper" (almost bouncing it on the surface). In both cases, the slight motion of the hackles gives the impression of life, which can be much more effective than a plain "dead drift."

The pesca a mosca Valsesiana flies are also somewhat similar to the North Country Spider style of soft hackle flies, although they are much more heavily hackled, tied on curved rather than straight shank hooks, and often use silk floss rather than silk thread for their bodies.

Like the Valsesian flies, Sakasa Kebari are hackled much more heavily than the North Country Spiders. I think that is a key design element. The sparse hackles of North County flies will fold back along the hook shank when the fly is worked, which forms a very convincing nymph shape but provides no resistance to being pulled through the water. The hackles of the Sakasa Kebari open up rather than fold down when the line is pulsed.

The hackle shape, and the heavy hackle, act like a sea anchor or drogue chute (an underwater parachute), resisting the pull of the line. That helps minimize line sag and allows a tenkara angler to keep his line tighter and off the water's surface. I believe that is the primary reason for the reversed hackle.

The Italian Valsesiana and the Japanese tenkara both utilize long rods with light lines tied to the rod tip. I do not believe it is coincidence that anglers in both counties developed reverse hackle flies. I think the rod, the line and the fly act together as a system, with the reverse hackle shape being an integral part of that system.

Tying The TenkaraBum Sakasa Kebari

The step-by-step sequence here shows such a fly, tied with a partridge feather for the hackle and Pearsall's Hot Orange Gossamer silk thread. I'll often use a brown feather for both the Partridge and Orange and the Partridge and Green, and a grey feather for the Partridge and Yellow and the Partridge and Red (which is not a standard pattern, but is an adaptation of Michael Hackney's favorite brookie fly, which uses a red thread body and grizzly hackle).

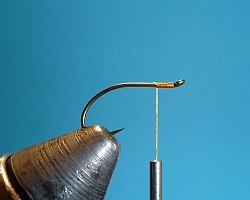

1. Start the thread at the eye and wrap back about 1/4 of the way to the bend. For a size 12 or 14 hook and Pearsall's Gossamer silk thread, I use 11 wraps.

2. Strip the fuzz off a partridge feather and tie it in on the top of the shank with the concave side up and the feather extending out over the hook bend. Do four or five thread wraps toward the hook eye, snip off the tip of the feather, and wrap to the hook eye. Then wrap back to the feather, lift the feather, and do about three wraps behind the feather.

3. Wrap the feather with each wrap just behind (towards the hook bend) the previous wrap, being very careful to not trap any barbs with your wraps. After each wrap gently stroke the feather barbs forward. Unlike the one to one and a half wraps used for the hackle of a North Country wet, make three wraps for a partridge feather, three or four with a hen pheasant feather. Some sakasa kebari flies, most notably the fly I call the Tenryu Kebari, are hackled more heavily than that. Tie off with three or four thread wraps. If you have wrapped the hackle properly, it should already have sufficient forward slant. Do not force it further forward. I now believe the fly shown has a bit too much forward slant. It reduces the mobility of the hackle (and at least to my eye, just looks wrong.) Tying it off often traps barbs on the wrong side of the thread (toward the bend). Clip these off, or, as Dr. Ishigaki does, just wrap the thread right over them (as long as they don't extend past the end of the body).

4. I now tie in a collar of peacock herl, as is done in the Takayama style. Take at one to three herls and holding it with both hands, catch the tying thread (starting with the herl between you and the thread). You will find better herl on a "peacock eyed stick" than in a package of "strung" herl. This fly shows only one herl. After fishing with the Tenryu Kebari, which has a much thicker thorax, I would now sugget using more than one.

5. Lift the herl behind the hook and gradually place it on the top of the hook shank, with the tying thread just behind the hackle.

6. Make about four touching wraps with the thread to secure the herl. Wrap the herl about three times, then tie it down and clip off the excess herl.

7. Wrap back to just before where you want the body to finish, and then back to the herl. Finally, wrap back to just beyond where you finished the body (by about three wraps), then do a four wrap whip finish with each wrap in front of the previous one. That should complete the smooth body.

Photo shows fly tied on a Daiichi 1250 barbless hook.

In addition to orange, which is perhaps the most popular "Partridge and ..." color, tie them also in yellow (which is an excellent imitation for sulfers), green (for any of the caddis species in which the pupae have green bodies), red (to see if Michael Hackney's favorite brookie fly becomes your favorite as well). Also tie them with bodies of peacock herl or pheasant tail because flies with those materials just seem to catch a lot of fish. They aren't as durable, but boy do they work. For a more durable fly with a color similar to pheasant tail, try using a brown horsehair for the body.

Yvon Chouinard wrote an article for Fly Fisherman magazine on the simplicity and effectiveness of a pheasant tail and partridge soft hackle, which he used as his only fly for a year.

The fly also works quite nicely when tied as a sakasa kebari. The fly

shown here used hen pheasant for the hackle, but partridge is just as

effective, easier to obtain and the smaller feather is more suitable for smaller flies.

After starting the thread and winding on the hackle, advance the thread to the bend and tie in about 4 pheasant tail barbs, bring the thread back to just behind the hackle in touching turns, then wind the pheasant tail up to where you have left the thread.

Tie off the pheasant tail, clip the tag ends, and then use your tying thread as a rib to reinforce the pheasant tail, winding in widely spaced turns back to the bend, just past the end of the pheasant tail wrappings. Tie a whip finish at the bend and you are done.

Green Silk

Green Silk Red Silk

Red Silk Black

Black Copper Wire

Copper WireSakasa Copperbari

Don't think they're just for trout.

Bluegills can't get enough of 'em. Yes, it took two flies! Glutton!

TenkaraBum Home > Tenkara Flies > Sakasa Kebari

“The bitterness of poor quality remains long after the sweetness of low price is forgotten” - Benjamin Franklin

"Be sure in casting, that your fly fall first into the water, for if the line fall first, it scares or frightens the fish..." -

Col. Robert Venables 1662

As age slows my pace, I will become more like the heron.

We've all had situations where seriously chewed up flies kept catching fish after fish after fish. It is no sin to tie flies that come off the vise looking seriously chewed up.

Warning:

The hooks are sharp.

The coffee's hot.

The fish are slippery when wet.

Beware of the Dogma

All the hooks sold on TenkaraBum.com, whether packaged as loose hooks or incorporated into flies, are sharp - or as Daiichi says on their hook packages, Dangerously Sharp. Some have barbs, which make removal from skin, eyes or clothing difficult. Wear eye protection. Wear a broad-brimmed hat. If you fish with or around children, bend down all hook barbs and make sure the children wear eye protection and broad-brimmed hats. Be aware of your back cast so no one gets hooked.

Also, all the rods sold on TenkaraBum.com will conduct electricity. Do not, under any circumstances, fish during a thunder storm. Consider any fishing rod to be a lightning rod! Fishing rods can and do get hit by lightning!

Coming Soon

What's in stock?

Kurenai II AR 33F

Kurenai II AR 39F

Furaibo TF39

Furaibo TF39TA

Nissin Oni Tenkara Line

If you enjoy spin fishing or baitcasting please visit my sister site Finesse-Fishing.com.